| | by admin | | posted on 2nd May 2023 in The English Revolution | | views 2628 | |

Between 1642 - 1651, the English Civil War Period saw King Charles I fight Parliament for control of England.

The term English Civil War Period is used to define the three separate wars that together formed England's civil war.

Ascending to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1625, Charles I believed in the divine right of kings – the idea that his right to rule came from God rather than any earthly authority. This belief led him to clash frequently with Parliament, whose approval was needed for him to raise funds.

Dissolving Parliament on several occasions, Charles I was angered by both its attacks on his ministers and its reluctance to provide him with money. In 1629, he elected to stop calling parliamentary sessions and began funding his rule through outdated taxes such as ship money and various fines. Charles I's approach angered both the population and the nobility. This period became known as the Eleven Years' Tyranny.

Next, in desperate need of money to contain rebelling Scots who were unhappy with his rule, Charles I was forced to recall Parliament. However, once reassembled, Parliament declined to give the King any money and instead set about curbing his powers as monarch of the realm.

Tensions were now like a powder keg ready to explode.

The First Civil War (1642 – 1646)

The powder-keg tensions finally erupted when Parliament ordered the Earl of Strafford, a close adviser of the king, to be executed for treason.

In January 1642, an angry Charles marched on Parliament with 400 men to arrest the five members he believed were responsible.

Failing to make the arrests, he withdrew to Oxford.

Through the summer of 1642, Charles and Parliament negotiated while all levels of society began to align in support of either side. While rural communities typically favoured the king, others such as the Royal Navy and many cities aligned themselves with Parliament.

On 22 August 1642, Charles raised his banner at Nottingham and commenced building an army. These efforts were matched by Parliament, who began assembling a force under the leadership of the Earl of Essex.

Unable to reach any resolution, the two sides clashed at the Battle of Edgehill in October 1642. Largely indecisive, the campaign ultimately resulted in Charles withdrawing once again to his wartime stronghold of Oxford. The following year saw Royalist forces secure much of Yorkshire as well as win a string of victories in western England.

However, in September 1643, Parliamentarian forces led by the Earl of Essex succeeded in forcing Charles to abandon the siege of Gloucester and won a victory at Newbury. As the fighting progressed, both sides sought reinforcements as Charles freed troops by making peace in Ireland while Parliament allied with Scotland.

Dubbed the Solemn League and Covenant, the alliance between Parliament and Scotland saw a Scottish army under the Earl of Leven enter northern England to reinforce Parliamentarian forces. Though Sir William Waller was beaten by Charles at Cropredy Bridge in June 1644, Parliamentarian and Scottish forces won a decisive victory at the Battle of Marston Moor the following month.

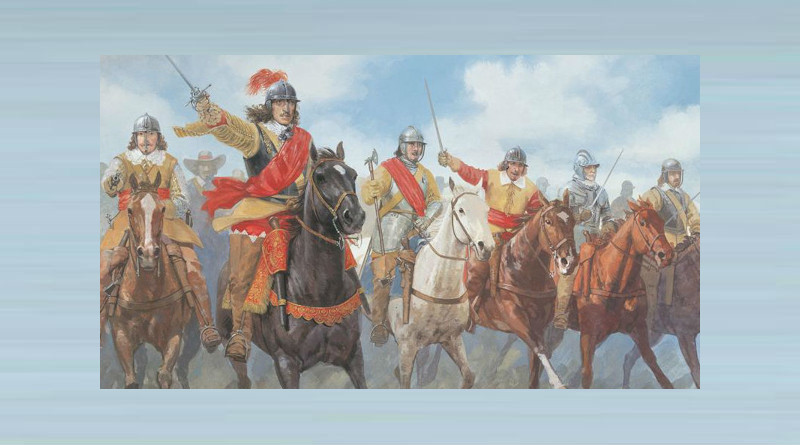

A key figure in the triumph at Marston Moor was cavalryman Oliver Cromwell. Having gained the upper hand, the Parliamentarians formed the professional New Model Army in 1645. Led by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Cromwell, this fighting force routed Charles at the Battle of Naseby. That same year, the New Model Army also secured victory at Langport in July.

Though he attempted to rebuild his forces, Charles's situation declined and in April 1646 he was forced to flee the siege of his Oxford stronghold. Riding north, he surrendered to the Scots at Southwell, who later handed him over to Parliament.

With Charles defeated, the victorious parties that had fought on the side of Parliament sought to establish a new government. In each case, they felt that the king's participation remained critical.

Interbellum (1646 – 1648)

Between the end of the first civil war and the beginning of the second, England entered a two-year period marked by political uncertainty. The Royalists had suffered a bitter blow, but it had not been decisive. Their authority was badly weakened, yet Charles I still remained king.

The only thing that had been settled was that the fate of the English Crown hung in the balance as rival factions vied for power.

The Second Civil War (1648 – 1649)

Playing rival groups off against one another, Charles signed an agreement known as the Engagement with Scottish rebels. The Engagement stipulated that the Scots would invade England on his behalf in exchange for the establishment of Presbyterianism, a form of Protestant Christianity, in their country.

The Scottish forces were ultimately defeated at Preston by Cromwell in August 1648, and the bulk of Royalist armies were destroyed.

Although, temporarily, Charles I still remained king.

The Third Civil War (1649 – 1651)

Angered by Charles I's negotiations with Scottish rebels, the New Model Army marched on Parliament and purged those who still favoured an association with the king. The remaining members, known as the Rump Parliament, ordered Charles I to be tried for treason.

Found guilty, Charles was beheaded on 30 January 1649. In the wake of the king's execution, Cromwell sailed for Ireland to eliminate resistance there. He won bloody victories at Drogheda and Wexford that autumn.

The following June saw the late king's son, Charles II, arrive in Scotland where he allied with Scottish forces. This compelled Cromwell to leave Ireland and campaign north.

Though Cromwell triumphed at Dunbar and Inverkeithing, he allowed Charles II's army to march south into England in 1651. In pursuit, Cromwell brought the last remaining Royalist forces to battle on 3 September at Worcester. Defeated, Charles II escaped to France, where he remained in exile until his restoration several years later.

With the final defeat of Royalist forces in 1651, power passed to the republican government of the Commonwealth of England.

The common people had won – but at what cost?

Thomas Hobbes, a contemporary philosopher, used the civil wars as a metaphor for the fragility of social order, describing life in such conditions as a “war of all against all”.

An estimated 180,000 people died from fighting, accidents and disease – approximately 3.6% of mid-17th-century England's population. Hunger was widespread and, despite a cessation in major hostilities, the country remained bitterly divided. Whatever England's post-war future might be, only one thing was clear – the nation would never be the same again.

© 2025 badger4peace | made in good faith with peace and solidarity 🕊️